Acute Kidney Injury

A Systematic Approach to Diagnosing Acute Kidney Injury

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common condition in hospitalized patients and is associated with increased mortality. Because of this, it is critical to diagnose AKI accurately, determine the underlying cause, and implement appropriate treatment to improve kidney function.

AKI is diagnosed based on changes in serum creatinine or urine output. The diagnostic criteria have changed over time, but we currently use the KDIGO criteria for AKI which are:

Serum creatinine increase of ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours

Serum creatinine increase of ≥1.5 times baseline within one week

UOP <0.5 mL/kg/hr for 6–12 hours,

If any of these criteria are met, you have AKI. Although the UOP criteria is less commonly used in clinical practice, it can identify AKI sooner than the serum Cr criteria. On the other hand, one important note is that BUN levels do not diagnose AKI. They are only surrogate markers of uremic solute accumulation that can cause uremic symptoms.

Diving down further, you may run across the concept of stages of AKI. While AKI is technically categorized into stages 1 to 3, with higher stages indicating progressively severe AKI, these classifications are primarily used for research purposes rather than actual clinical practice. The primary goal of AKI diagnostic criteria is to find AKI, identify the cause, and reverse it if possible.

Why AKI Matters

In addition to it’s obvious effects on kidney function, AKI is an independent risk factor for mortality. Even a small creatinine rise of 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours is associated with increased mortality. The severity of AKI further correlates with worse outcomes.

Stage 1 AKI has an odds ratio of 2.2 for mortality.

Stage 2 AKI increases the risk further, with an odds ratio of 6.1.

Stage 3 AKI carries the highest risk, with an odds ratio of 6.6.

One study found that the overall mortality rate associated with AKI was approximately 45%. This underscores the urgency of timely recognition and intervention.

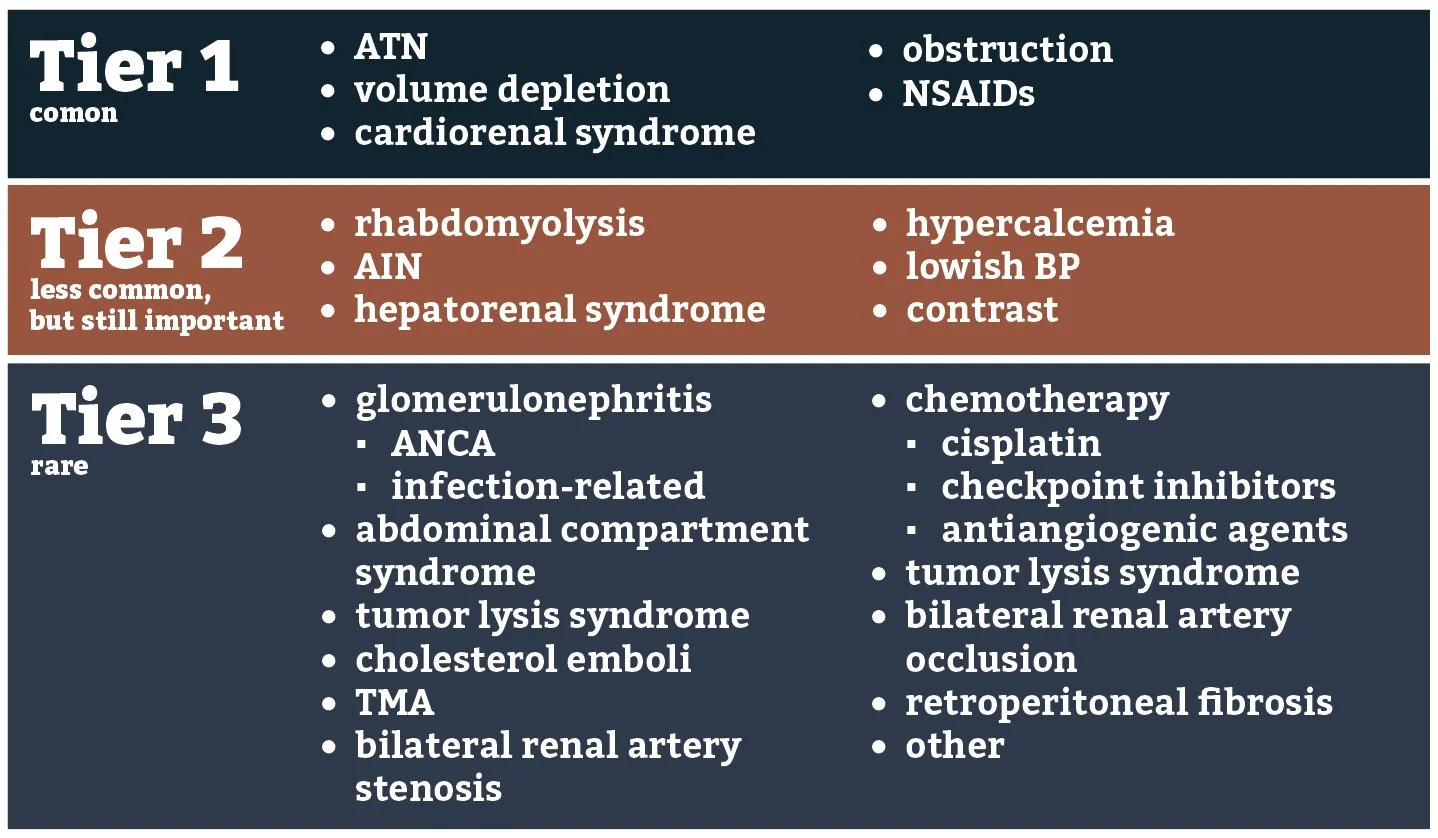

A Tiered Approach to Diagnosing AKI

Our goal is to diagnose AKI and reverse the cause. The challenge is that the hospital is busy and therefore it is essential to efficiently evaluate for all the possibilities for AKI in a patient. We need several lenses with which to view potential AKI diagnoses, beginning with the most common causes first and then moving to more rare etiologies only if the common ones have been ruled out. In addition to allowing yourself to forget about the zebras while you diagnose horses on a routine basis, this Bayesian approach refines your differential diagnosis to increase the probability that a lab test or subtle exam finding suggests a rare cause of AKI. It allows you to come up with presumptive diagnoses like rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis or acute bilateral renal artery occlusion within minutes, not hours. First, I think that a tiered approach to diagnosis is best, which looks at common causes of AKI first. If common causes are not the culprit on initial evaluation, then alternative causes are then considered. This not makes the diagnostic process more efficient and allows you to consider rare causes of AKI, not by finding a smoking gun, but by noticing subtle clues and allowing you take part in the art of medicine. When you are evaluating your patient, get an overall view of why they are in the hospital and what the active issues are. After that, begin a deep dive into potential causes of AKI beginning two days before AKI was diagnosed. Look for clues that could suggest a particular cause of AKI and then correlate them with changes in the creatinine.

Tier 1: Common Causes of AKI

Most cases of AKI encountered in the hospital belong to Tier 1, where we first think about common etiologies that present in a common fashion. These include:

Acute Tubular Necrosis (ATN)

Volume depletion

Cardiorenal syndrome

Urinary obstruction

NSAID-associated AKI (though NSAIDs rarely cause AKI by themselves, they often exacerbate an existing renal insult, such as volume depletion or hypotension).

To evaluate for Tier 1 causes of AKI, clinicians should obtain a detailed history, focusing on chronic conditions, acute medical events, and medication exposures. For each consult, you should know a patient’s past medical history, chief complaint for the hospitalization, baseline kidney function, the primary reason for their hospitalization, acute issues initially addressed, and how the focus of care has changed through the hospitalization. Testing is pretty basic in this stage:

Basic metabolic panel (BMP)

Urinalysis (UA)

Urine sediment personally viewed under a microscope

Kidney ultrasound

A urinalysis is useful for several reasons. It may give you several clues. If you see glucose in the urine, it may let you know that osmotic diuresis has been a factor in causing volume depletion. If you see ketones, this may clue you into the fact that the patient has not been eating and has starvation ketosis and volume depletion. If the specific gravity is 1.030, then this may suggest volume depletion as well. Although it’s rare for a UA to show granular casts, this could suggest ATN. Lastly, if you see unexplained RBCs or WBCs in the urine, it will clue you into looking for dysmorphic RBCs (for glomerulonephritis) or WBC casts (for acute interstitial nephritis), respectively, and this may push you into tier 2 or tier 3 faster.

Viewing the urine under a microscope is invaluable. Most often, we use it to look for the presence or absence of ATN. When you see ATN, this can give you a diagnosis as the sole cause of AKI. It can also help you if the patient has concomitant volume depletion, as the additional presence of ATN will blunt the effect of IV fluids on Cr improvement. Lastly, if a patient has a heart failure exacerbation as well as ATN, you will not see the typical improvement in Cr after diuresis seen in cardiorenal syndrome – you will have to wait for ATN to heal first. One thing to remember is the fact that in up to 25% of cases, a patient with ATN may not have granular casts on the urine sediment on the first viewing but will on a subsequent 2nd or 3rd examination.

Imaging with a kidney ultrasound should be performed unless the diagnosis is entirely certain, such as a patient whose creatinine is already improving in resolving AKI from volume depletion. Overall, a kidney ultrasound poses essentially no risk to the patient, and it is unacceptable to miss obstruction.

Based on this testing, here is how we diagnose each etiology in tier 1:

ATN: diagnosed based on urine sediment findings. After this, correlate the clinical course of their AKI to find the cause of ATN

Sepsis with or without hypotension

Hypotension

NSAIDs + another insult

Multiple insults in fragile individual

Influenza or COVID

Normotensive ATN

Volume depletion + other insult

Hypotension after intubation

Surgery

Volume depletion: diagnosed based on history, exam, ruling out ATN on the urine sediment, ruling out obstruction. After that, we decide if the patient will tolerate IV fluids. If the Cr improves with IV fluids, then we know that volume depletion was the cause. There is no utility to using the fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) or fractional excretion of urea.

Cardiorenal syndrome: diagnosed in a patient with a heart failure exacerbation with signs of volume overload. ATN and obstruction should be ruled out.

Obstruction: diagnosed based on kidney ultrasound and/or bladder ultrasound

NSAIDs: It is rare for these to cause AKI on their own. A good way to think about NSAIDs is by thinking about them with a two-hit model type of thinking. Patients usually have AKI involving NSAIDs when there is concomitant volume depletion, low blood pressure, or something else.

High dose NSAIDs are associated with AKI in transplant patients whereas low dose NSAIDs are not. High dose >6 months of use triples the risk of AKI. Even 7d use slightly increases (OR 1.05) risk of AKI. High dose in this study is defined by daily uses of ibuprofen >1200mg; naproxen >100mg; diclofenac >100mg; meloxicam >7.5mg

Combining either RAASi or diuretics with NSAIDs gives you a 60% increased risk of AKI

Celexcocib has lower rates of AKI than ibuprofen (0.7% vs 1.1%; HR 0.61, but not naproxen, per the PRECISION Trial

In healthy young and middle-aged adults, high doses of NSAIDs (as in >100mg naproxen or >1200-2400mg ibuprofen at least 7d a month for 6 months) gives a 20% increased risk of AKI or CKD compared to those who do not take NSAIDs. Use of NSAIDs lower than these doses does not give an increased risk.

Tier 2: Less Common but Important Causes of AKI

If Tier 1 causes are ruled out, clinicians should consider Tier 2 diagnoses, which are less common but still fairly frequently. These include:

Rhabdomyolysis

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN)

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS)

Intraarterial contrast

Hypercalcemia

Blood pressure beneath the autoregulatory threshold of the kidneys

Testing for these tier two diagnoses is still relatively straightforward. We of course stil heavily rely on the clinical context, as recent left heart catheterizations suggest contrast associated nephropathy. Testing includes:

CK level

Urine sediment examination

CBC with differential

Calcium level

Based on this testing, this is how we diagnose things in tier 2:

Rhabdomyolysis: can easily be found by a CK level of 15,000 or at least 5,000 with concomitant volume depletion.

Acute interstitial nephritis: this can be difficult to diagnose. Although textbook patients typically have a triad of fever, rash, and peripheral eosinophilia, the presence of these is variable depending on the medication that cause the AKI. To diagnose AIN, you really have to rule out alternative diagnoses and hopefully, you will be able to capture a WBC cast in the setting of sterile urine. A CBC with a differential showing peripheral eosinophilia makes it more likely you have AIN. These findings will lead you to consider a kidney biopsy, which will ultimately clench the diagnosis. Urine eosinophils aren’t helpful and only provide a coinflip probability to helping with the diagnosis.

Hepatorenal syndrome: consider this in a cirrhotic patient with ascites who develops AKI not due to an obvious cause. Typically though, HRS happens in patients with decompensated cirrhosis who have become diuretic-resistant and rely on paracentesis. The formal diagnostic criteria was made by the International Club of Ascites:

AKI as diagnosed by KDIGO criteria

Patients with cirrhosis and ascites

Absence of an alternative cause of AKI including:

Absence of shock

No recent nephrotoxic medication use

No cause of AKI seen on kidney ultrasound

No urine sediment findings that suggest an alternative cause of AKI, including granular casts showing ATN.

In patients without volume overload, if the kidney function does not improve after two days of diuretic cessation along with volume expansion with albumin 25% given at a dose of 1g/kg/day (max dose 100g/day)

Intraarterial contrast: based on clinical context and ruling out other causes

Hypercalcemia: will be obvious on routine testing.

Blood pressure beneath the hemodynamic autoregulatory threshold: this can be a subtle cause of worsening kidney function. A classic presentation is someone who’s been in the hospital for weeks and is just waiting on placement. You may notice that every other day, their serum Cr increases by 0.1mg/dL and they often have a SBP <120 or a DBP <60. If this is the case, reduce BP meds to a SBP 120-140mmHg and watch their Cr improve. Of course, if this happens outside of the hospital, their baseline Cr of 1.5 from weeks ago may have worsened to 2.5 when evaluated on initial presentation to the ED.

Tier 3: Rare Causes of AKI

After ruling out Tier 1 and Tier 2 causes, you are now left with rare causes of AKI. There is really no standard testing for these and further workup is based on clinical context. This is how you consider and workup the following rare conditions:

Glomerulonephrits, in general: suspect in a patient with dysmorphic RBCs in the urine and/or petechial rash. Also consider in patients with AKI and hemoptysis. In these patients, order glomerulonephritis serology and utilize a kidney biopsy to make the diagnosis.

ANCA vasculitis should be a top consideration in someone with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. If serology comes back with MPO+ and PR3+ ANCA vasculitis, consider hydralazine-induced ANCA vasculitis

Anticoagulant nephropathy: Consider this in someone with gross hematuria who recently started an anticoagulant. The proportion of dysmorphic RBCs in the urine sediment may be massive.

Checkpoint inhibitor-associated AKI: Consider it in someone on a checkpoint inhibitor. The median onset is 120 days after starting the medication. Of patients with ICI-AKI, 90% have AIN as the cause of AKI.

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS): based on laboratory and clinical Cairo-Bishop criteria

Cholesterol emboli: Consider them in those with recent arterial procedures with digital ischemia. Most patients will have a subacute presentation that begins 6 weeks after their procedure.

Amphotericin B: The usual onset is 7 days after the medication is started.

Other nephrotoxic medications: such as gentamicin or amikacin. Clinical context is the most important consideration for this.

Thrombotic microangiopathy: consider in someone with thrombocytopenia and AKI. A peripheral smear showing schistocytes is sufficient to consult hem/onc and possible plasma exchange.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis: this is rare, but it happens. This can cause urinary obstruction even with no hydronephrosis on a kidney ultrasound. CT imaging may show a mass-like encasement of the aorta. A true diagnosis is made based on an improvement in kidney function after percutaneous nephrostomy tubes are placed or the ureters are stented.

Abdominal compartment syndrome: can happen in patients with ascites or pancreatitis, or other intraabdominal pathology. Bladder pressure will consistently be >20cm H2O

Acute bilateral renal artery occlusion is very rare, but it is considered in patients with abdominal aortic grafts or antiphospholipid syndrome who, after a Foley catheter is placed, have absolutely no urine in the catheter—not even a drop. You can get an LDH initially. If it is high, a CT angiogram of the abdomen showing occlusion confirms the diagnosis.

Renal artery stenosis: consider in a patient who has AKI with diuresis that seems out-of-proportion to the level of diuresis. Test for this with a renal doppler. Specifically, only patients with a single kidney and RAS or those with bilateral RAS will present this way. Keep in mind that patients with bilateral RAS or RAS in a single kidney will be particularly susceptible to diuretics and may have acute kidney injury at proportion to the level of diuretic dosing.

Conclusion

The tiered approach allows for a logical, efficient workup of AKI, ensuring common causes are addressed before rare diagnoses are considered.

Tier 1 focuses on common, straightforward causes.

Tier 2 expands to less frequent but important conditions requiring targeted testing.

Tier 3 explores rare diseases that demand specialized evaluation and expertise.

By following this structured method, clinicians can quickly identify the cause of AKI, optimize treatment, and improve patient outcomes.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do. Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.